In today’s volatile global landscape, geopolitical risks are no longer distant headlines—they are boardroom concerns. For Turkish companies, these risks are particularly acute. The war in Ukraine, unrest in the Middle East, supply chain fragmentation, energy instability, and rising protectionism are just a few examples of how geopolitical dynamics now shape business strategy, investment decisions, and even operational continuity.

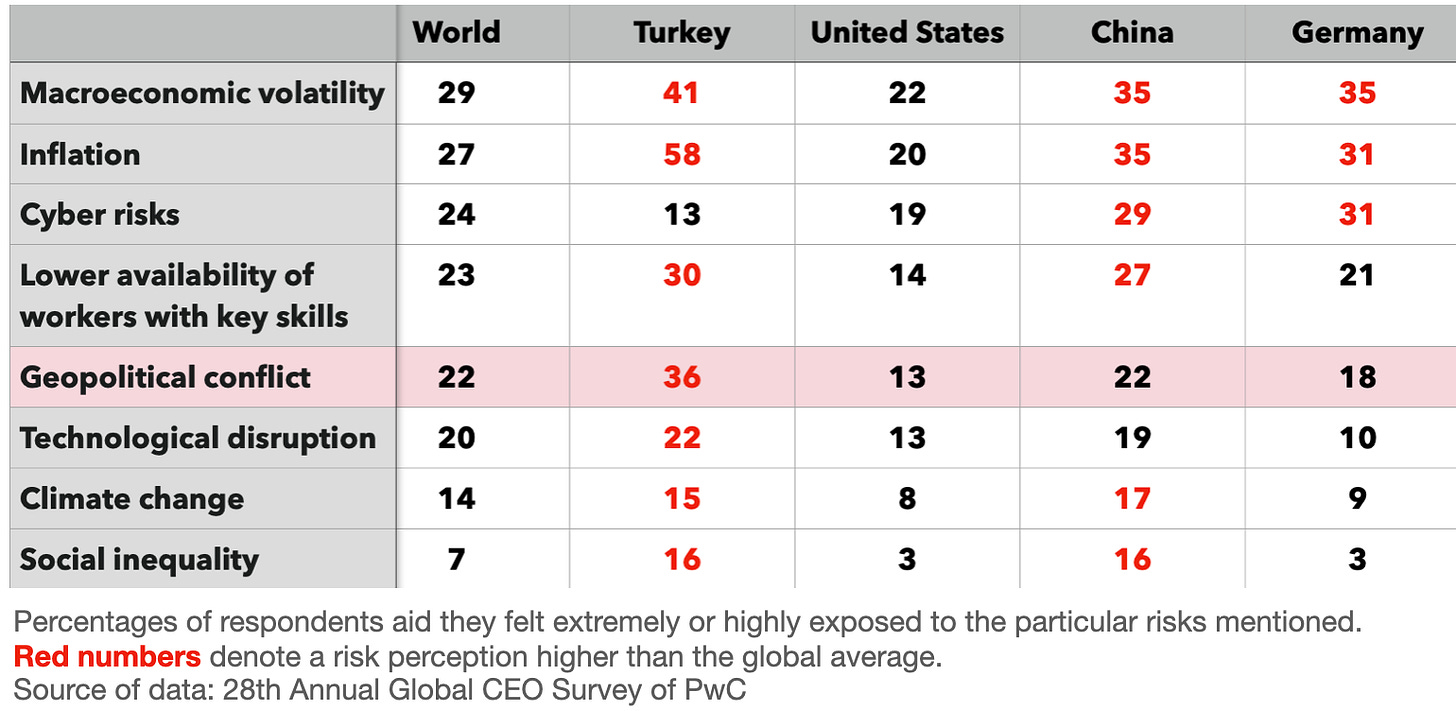

A useful snapshot of how global business leaders are viewing the world today comes from the PwC 2025 Global CEO Survey, which draws on the perspectives of 4,701 CEOs across 109 countries—including 88 from Turkiye. One of the central questions asked was how exposed they believe their companies will be to key threats in the next 12 months. These threats included macroeconomic volatility, inflation, cyber risks, skills shortages, technological disruption, climate change, social inequality, and geopolitical conflict.

What’s particularly striking is how much more concerned Turkish CEOs are about geopolitical conflict compared to their global peers. While only 22% of CEOs globally said they felt extremely or highly exposed to geopolitical conflict, the figure was 36% among Turkish CEOs—more than one-third.

This isn’t surprising when you consider Turkiye’s geographical and geopolitical position. Situated at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, Turkiye borders or maintains deep economic ties with some of the most conflict-prone regions in the world. Turkish foreign direct investment and construction services—industries in which Turkish firms are global players—are heavily concentrated in areas such as the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia. Moreover, Turkiye’s complex relationship with Russia, including strong trade, energy, and tourism links, adds another layer of geopolitical exposure.

But the concern doesn’t stop at geopolitical conflict. Turkish CEOs report a higher-than-global-average sense of exposure in 7 out of the 8 risk areas surveyed—everything except cyber risks. This reveals a broader insight: risk domains are increasingly interconnected. Geopolitical uncertainty fuels inflation and macroeconomic instability. Technological disruption exacerbates skills shortages. Social inequality can be a catalyst for unrest. In today’s world, no risk is isolated.

Interestingly, while the survey did not ask CEOs what they are actively doing to mitigate these geopolitical risks, it did ask where they see future growth opportunities. Turkish CEOs expect to find growth in major markets such as the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, and China—consistent with global trends. However, Turkish CEOs also diverge from their global counterparts by naming Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia, and Italy as potential growth markets. These choices offer further evidence that Turkish business leaders are keenly attuned to geopolitical realities and are adapting their market strategies accordingly.

So where does this leave us?

It’s clear that awareness of geopolitical risk is rising in Turkiye’s business community. But awareness must now be matched with action. Concern alone doesn’t build resilience. The next step is translating awareness into capability:

- Supply chain diversification—already underway for many exporters—should now be paired with market diversification, especially into regions increasingly less dependent on traditional Western demand.

- Geopolitical monitoring can no longer be outsourced to embassies or think tanks; it needs to become a core business function.

- Scenario planning must go beyond hypothetical risk maps and be integrated into real-time decision-making.

- Strategic alliances, especially with regional partners, must evolve from ad hoc deals to long-term risk-sharing arrangements.

The conventional wisdom is that geopolitical instability is a drag on business. however, not every geopolitical shift spells disaster. Every risk comes with a potential opportunity. As global alliances shift, new trade corridors emerge, regional investments rise, and previously overlooked markets become more viable. Turkish companies—seasoned by decades of operating in challenging environments—are well-positioned to seize these opportunities, provided they approach them with strategic foresight and robust risk management.

In short, Turkish CEOs are right to be concerned. But concern is only the first step. The challenge now is to build institutional muscle around geopolitical risk, not just react to it. Navigating this new era of fragmentation will require bold thinking, agility, and a willingness to see opportunity in uncertainty. For those that do, what looks like fragmentation may in fact become a source of long-term competitive strength.